-

-

Telefone:

11 97853 5494 -

E-mail:

[email protected]

Idioma:

PT-BR

Idioma:

ESP

Idioma:

ENG

O iminente colapso da publicidade digital (em inglês)

Fonte: Marker

12 de outubro de 2021

Digital ad fraud could be a $150 billion business by 2025, which would make it the largest criminal enterprise after the drug trade

If Edward Snowden was injected with a megadose of Super Soldier Serum, he’d look something like Frances Haugen. Perhaps Haugen’s disclosures — that among so many other evils, Zuckerberg knew Facebook’s products “harm children” — means that Facebook has crossed the wrong cowboys, specifically … cowgirls who are moms. MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) finally galvanized the nation against the scourge of drunk driving in the 1980s — will MAMS (Mothers Against Mark and Sheryl) bring down the Zuck and his merry band of mendacious fucks?

But that is not what this post is about.

Facebook — all social media, really — is the nicotine, the dopa drip of outrage and baby pictures that keeps us coming back for more. But the carcinogen, the thing that should have warning labels slapped all over it and congressional hearings devoted to it, is … an algorithm-driven advertising model.

Ad-supported media has a long history, and it’s not all bad. Alcoa paid for Edward R. Murrow’s airtime, Woodward and Bernstein’s Washington Post relied on advertisers, and on Sunday night, Frances Haugen waited patiently for a Jack in the Box ad to run before she stepped out of the 60 Minutes phone booth in her superhero cape.

Even in traditional media, advertising has always been a problem — what stories did Murrow avoid while Alcoa was paying the bills? But on digital media, advertising has more potential and more power, and it corrupts the media businesses that rely on it. Digital advertising has exploded; even after a Covid-19 dip, it accounts for nearly half of all U.S. advertising spend.

Big Little Lies

This torrent of money is what fuels Facebook, YouTube, and the rest of the teenage-dystopia-industrial-complex. The transformation of media into social media into a surveillance-based attention economy is a direct result of the digital ad model. But there’s a second externality, and while it’s historically received less attention than the ill effects of algorithmic enragement bias, it’s a problem that’s grown in the shadows into a multibillion-dollar beast. Fraud.

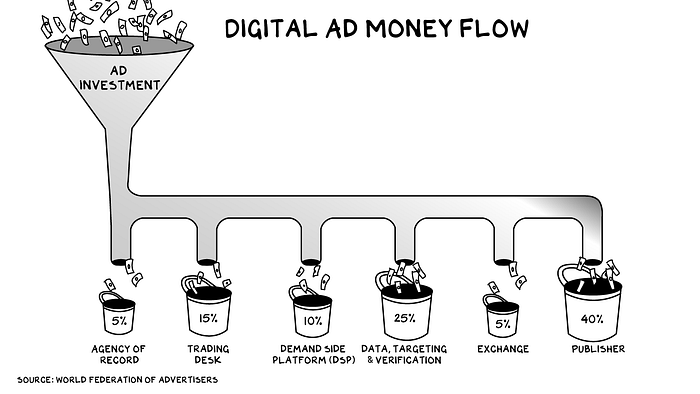

The digital advertising industry is a Rube Goldberg machine of platforms, agencies, exchanges, and other middlemen. I’d explain it to you here, but a) I don’t understand it, and b) you don’t want me to. The number that matters is 89%. That’s the percentage of dollars spent on “programmatic” advertising. Ads bought by algorithm.

In a programmatic ad buy, the client — Nike or Nissan or Novartis, acting through an agency, the first of many middlemen — provides the ad itself and sets up criteria for who it wants to see it (e.g. 36- to 42-year-old Hispanic males with Crohn’s disease in the final year of their auto lease). Then a series of automated processes place many thousands of copies of the ad on many different websites, anywhere the algorithms believe the ad will be seen by people meeting the target profile.

That’s lots of palms to be greased. Lots of opportunities for people to cheat, and enough complexity that this cheating is difficult to detect. Especially if the cheating only makes the system more money.

The basic cheat is the fake view. An ad is reported as being served to humans, when it was actually only “seen” by a bot, or by a person in a “click farm” tapping at dozens of screens, or by nothing at all. Networks of fake websites fool the algorithms into believing they are real publications. Measurements of the impact are all over the map, but we know fraud is pervasive. By one estimate, 88% of digital ad clicks are fake.

Publishers and the middlemen who place ads with them tout all sorts of supposed fraud-detection technology, but industry experts say it’s largely worthless. Of course it is. These players benefit from inflated ad views — why would they suppress them? In 2008, Newsweek Media Group infected its own fraud-detection system with malware so it could charge advertisers for bot-generated traffic on some of its websites. Recently collapsed Ozy Media was a heavy buyer of fake traffic, and we haven’t seen the last Ozy-type scandal.

Even ads that do make it to real humans are not all that likely to be seen by the people the advertiser is looking for. This was the core promise of digital advertising — saving modern-day John Wannamakers the half of their ad budget that was wasted on uninterested consumers. But there’s increasing evidence that this promise was the biggest fraud of all.

A study by MIT professor Catherine Tucker found that even targeting something as basic as gender was unsuccessful more than half the time (i.e., it was worse than random). A Nielsen analysis of a household-income-adjusted ad campaign found that only 25% of its ads were reaching the right households. As much as 65% of location-targeted ad spend is wasted. Plaintiffs in a class-action suit against Facebook have alleged its targeting algorithm’s “accuracy” was between 9% and 41%, and quoted internal Facebook emails describing the company’s targeting as “crap” and “abysmal.”

And the technology that enables even this lousy tracking, the digital cookie, is on the way out. Cookies are short pieces of code websites leave behind on your computer so they can follow you across the Internet. But one adtech firm found that 64% of its tracking cookies are either blocked or deleted by web browsers. Apple recently updated iOS to require would-be ad trackers to obtain a user’s permission before dropping a cookie. Google’s Chrome (which commands 60% of the browser market) will block third-party cookies altogether by 2023. Although that cloud has a dark lining: Google is replacing cookies with its own proprietary system that will centralize ad tracking under its exclusive control. What could possibly go wrong?

Google and Facebook are the dominant players in this business. They’re huge publishers (capturing over half the digital ad dollars), and also the leaders in many of the upstream categories in the programmatic ad infrastructure. Google, for example, owns the largest digital ad marketplace, DoubleClick Ad Exchange.

Fraud is rampant in other areas of the digital ad business. Influencers can buy fake followers by the truckload — roughly 20% of them are fake. Approximately 40% of Donald Trump’s followers are likely bots. Social media platforms are rife with cats and bots: Facebook admits to shutting down billions of fake accounts on its platform every year. Even app store installs are fake. Bots/click-farmers download 1 in 5 iOS apps. On the Android platform it’s 1 in 4.

This problem pales in comparison to Facebook’s rage and confirmation bias debacle, but it’s still a serious economic issue. Criminality is a cost ultimately borne by consumers, and crime begets crime. Digital ad fraud could be a $150 billion business by 2025, which would make it the largest criminal enterprise after the drug trade — and it fuels the same digital criminal underground responsible for industrial espionage, ransomware, and identity theft.

We need externally imposed and enforced industry standards on transparency in advertising. Expecting these conflicted middlemen to self-regulate is (generously) naïve.

And we should consider taxing algorithms that serve ads and content. We tax cigarettes and alcohol to suppress their use and fund policies to address some of their externalities. Programmatic ad buying, similar to other media buys, can be good/bad, and that’s a component of business. But this is addiction, and it’s hurting all of us. It’s time for an intervention.

Don Draper, RIP

That’s what should happen. What will happen? The edifice of digital advertising is unstable and likely to collapse. The promise of measurable ad spend has been crack for chief marketing officers. That algorithm-driven media was destroying our commonwealth by accelerating the spread of misinformation and division wasn’t enough to give them pause. But now that they’re realizing that promise was a lie, some are putting down the pipe. Several large advertisers have made deep cuts in their digital ad budget — including Procter & Gamble (cut $200M), JPMorgan Chase (slashed ad reach by 99%), Uber (cut $200M), and eBay (cut $100M) — and seen little or no measurable impact on their business. Other large companies are building programmatic ad capabilities in house, figuring they can trust the tech if they built it.

These firms already have huge brands and global distribution, partnerships, and other means to sustain awareness. It’s possible to build a strong brand without advertising. Tesla is the most recent example, but not every company makes a revolutionary product in a highly visible consumer category.

Digital advertising promised small and mid-size businesses a way to take a small ad budget and increase efficiency. And where do these businesses feel they have to spend their money? The Facebook and Google duopoly. Which brings us back to where we started: mendacious …

Confira o artigo no site Marker.

Compartilhar

Veja Também

Nada mexe mais com o coração do brasileiro do que uma Copa

Certa vez, um CEO de uma grande empresa foi perguntado por um estudante de marketing: ”Se a sua empresa não existisse, o que mudaria no mundo?” O poderoso CEO passou a noite em claro, pensando numa resposta que fizesse sentido. Não encontrou. Por isso, começou a repensar toda a existência e o propósito de sua […]Como trabalhar – e impulsionar – o valor da marca pessoal?

Uma das missões que permeiam o cotidiano dos profissionais da indústria da comunicação, tanto os de agências quanto os de anunciantes, é fazer com que as marcas para as quais trabalham sejam vistas com admiração e desejo pelos consumidores. Fazer com que marcas de empresa sejam mais valorizadas é, portanto, um trabalho recorrente. Mas, para […]Sobre

A ABAP agora é Espaço de Articulação Coletiva do Ecossistema Publicitário. Fundada em 1º de agosto de 1949, a ABAP segue trabalhando em prol dos interesses das agências de publicidade junto à indústria da comunicação, poderes constituídos, mercado e sociedade.

Dentre suas realizações estão a cofundação do Conselho Nacional de Autorregulamentação Publicitária (CONAR), do Fórum da Autorregulação do Mercado Publicitário (CENP), do Instituto Verificador de Comunicação (IVC) e do Instituto Palavra Aberta.

Telefone:

11 97853 5494E-mail:

[email protected]